Byzantine icons and Western painting icons represent two distinct artistic and theological traditions within the broader scope of Christian sacred art. These artistic forms, while both focused on conveying religious devotion and spiritual truths, diverge significantly in terms of their aesthetic choices, underlying theological assumptions, cultural contexts, and techniques. This article provides an analytical and comparative examination of the key differences between Byzantine icons and Western painting icons, evaluating their distinctive qualities from historical, stylistic, symbolic, and theological perspectives.

©VENIS STUDIOS

-

Historical Context and Development

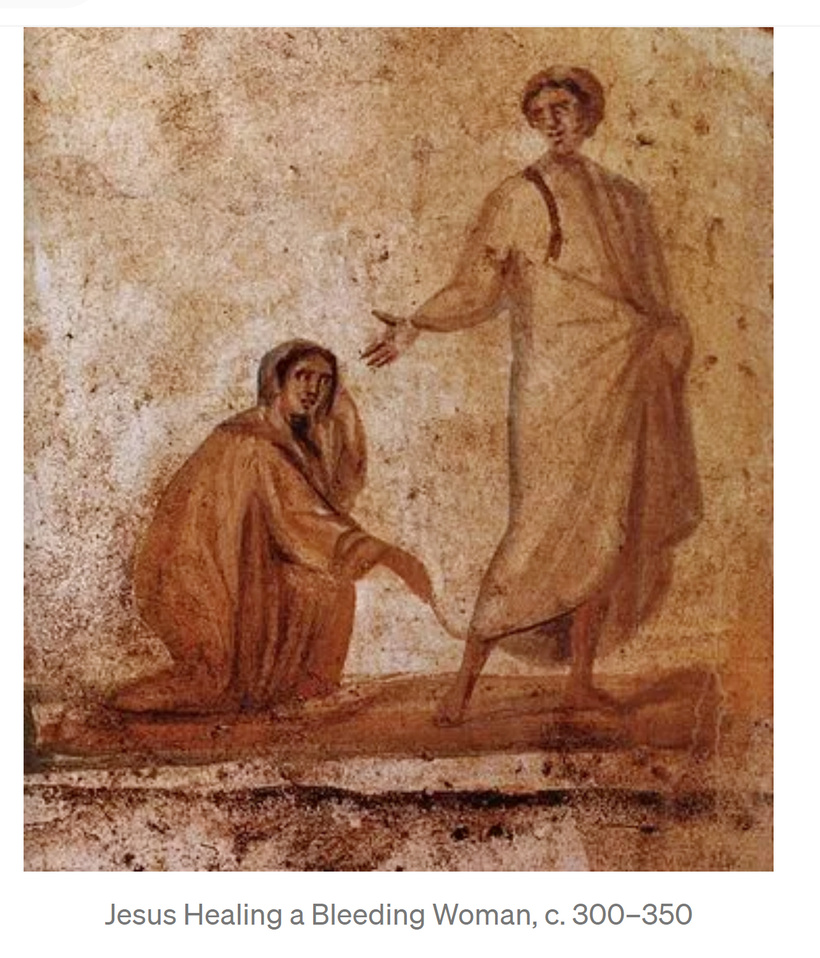

The origin and evolution of Byzantine icons can be traced back to the early Christian period in the Eastern Roman Empire, primarily from the 4th to the 15th centuries. Icons emerged as a dominant form of religious imagery in the Eastern Orthodox Church, driven by the theological framework of the Eastern Christian tradition. The Iconoclastic Controversy (8th-9th centuries) played a pivotal role in shaping Byzantine iconography by affirming the legitimacy of religious images, emphasizing that icons were not simply representations but embodied the divine presence. The eventual development of a strict iconographic system ensured that each image adhered to a precise set of rules to preserve the sanctity of the divine subject.

In contrast, Western painting icons, especially during the Medieval and Renaissance periods, developed in response to the broader cultural and intellectual movements that emerged in the Latin West. During the Middle Ages, religious art in Western Europe was primarily functional, serving devotional purposes and enhancing liturgical practices. However, with the advent of the Renaissance, the approach to sacred imagery experienced a profound shift as Western artists embraced humanism and the study of classical antiquity, leading to a renewed focus on realism and the natural world. The Protestant Reformation (16th century) also influenced the production and use of religious art in the West, especially with the rise of iconoclasm, which led to a diminishing role of religious imagery in Protestant regions.

©VENIS STUDIOS

-

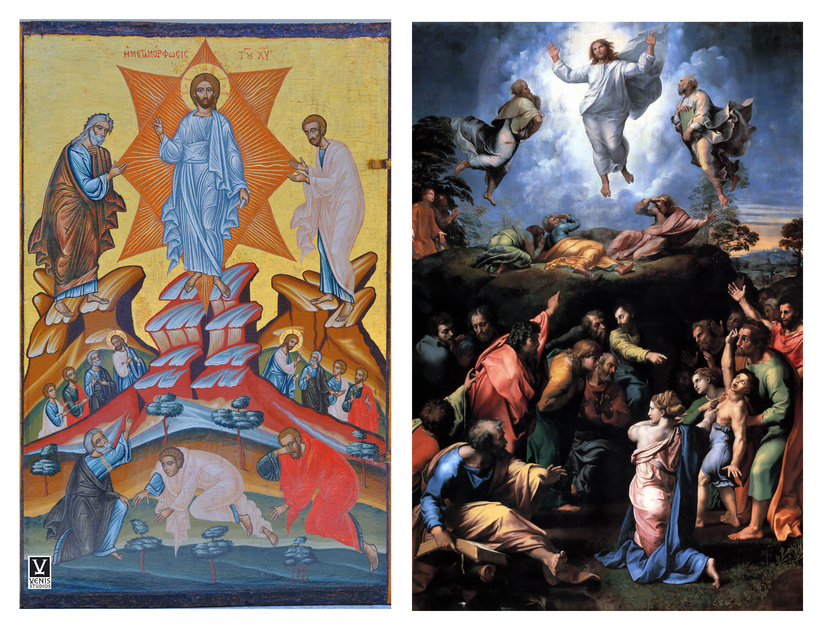

Stylistic and Aesthetic Differences

A defining feature of Byzantine icons is their distinctive visual style, characterized by formalism, abstraction, and symbolism. The figures in Byzantine icons are typically elongated and exhibit minimal attention to naturalistic detail or anatomical accuracy. Proportions are idealized rather than realistic, and the figures are often rendered frontally to emphasize the divine nature of the subjects depicted. The background is frequently gilded with gold leaf to suggest the realm of eternity, reinforcing the notion that the icon is not part of the earthly, temporal world but exists in the divine, heavenly realm.

Western painting icons, particularly from the Renaissance onward, diverged sharply in their approach to naturalism and perspective. Renaissance artists, such as Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael, and Michelangelo, emphasized the accurate depiction of the human figure based on the principles of classical antiquity and anatomical studies. These artists applied linear perspective to create a sense of depth and three-dimensionality, thereby fostering a more immersive, realistic visual experience. Unlike Byzantine icons, where the figures often appear passive and serene, Western painting icons convey greater emotional depth, with figures expressing a range of human emotions and psychological states. This shift was not merely technical but also philosophically rooted in the growing humanist interest in the lived experience of the human subject.

-

Theological Significance and Symbolism

The theological intent behind Byzantine icons is central to their purpose and form. In the Eastern Orthodox tradition, icons are not seen as mere representations of religious figures but as sacred vessels that mediate the divine presence. The icon is viewed as a window to the divine, a bridge between the earthly and the heavenly. The use of stylization and abstraction in Byzantine icons reflects the Orthodox belief that God transcends the material world. The iconographer’s task was not to replicate physical likeness but to convey the divine essence, which often led to the adoption of highly codified iconographic conventions. Christ, for example, is typically depicted with a halo and certain symbolic gestures, which are meant to convey his divine nature rather than his human likeness.

In contrast, Western painting icons, particularly those of the Renaissance, were deeply influenced by the growing desire to humanize religious subjects. While Western art maintained its theological foundation, it also sought to render the divine in a more relatable form. The use of realism and perspective in Western art emphasized the humanity of Christ and the saints, portraying them not as detached divine beings but as figures with whom the viewer could empathize. This shift towards humanism meant that Western icons became more narrative, often telling stories from the Bible with a focus on human emotions, actions, and social contexts.

©VENIS STUDIOS

-

The Role of Iconography and Narrative

Byzantine icons adhere to a strict iconographic code that dictates the placement, posture, and symbols of each figure. The icon is conceived as a spiritual tool designed to facilitate prayer, meditation, and communion with the divine. Icons rarely depict dynamic narratives in the sense that Western paintings do. Rather, they are structured to provide visual clues about the heavenly order, using symbols such as halos, specific colors, and fixed gestures to signify the roles and attributes of saints and Christ. For instance, the Virgin Mary is often depicted with a red robe, symbolizing her humanity, and a blue cloak, representing her divine nature.

In contrast, Western painting icons evolved to be more narrative-driven, particularly during the Renaissance. Artists like Caravaggio, Titian, and El Greco utilized the visual space to create dynamic scenes filled with emotional and dramatic tension. These works aimed to educate the viewer not just about the divine, but about human history, moral teachings, and theological virtues. The use of perspective and chiaroscuro allowed Western artists to depict biblical events in a more lifelike manner, which served as a form of visual storytelling. The incorporation of emotional expression in figures allowed viewers to engage with the artwork not only on a spiritual level but on an emotional and psychological one as well.

-

Techniques and Materials

The techniques and materials used in Byzantine icons are highly specialized and have remained relatively consistent over the centuries. Icons were typically painted on wooden panels, often using egg tempera as the primary medium, with multiple layers of paint applied over a gesso ground. Gold leaf was commonly used to accentuate the divine light and to create a glowing, ethereal background. The process of creating an icon was meticulous, often involving several stages, including the preparation of the wood, the application of gesso, the drawing of the design, and the application of paint. The gold leaf, applied in thin sheets, enhanced the spiritual quality of the icon and symbolized the eternal nature of God.

In contrast, Western painting icons, particularly after the Renaissance, saw the widespread use of oil paint, which allowed for greater color depth, subtle gradation of light, and more detailed textures. The use of oil paint enabled artists to create richer, more detailed depictions of human subjects and landscapes. Additionally, the use of canvas as a support medium became common in the West, replacing wooden panels as the primary surface for religious paintings. Oil painting allowed for the development of techniques such as sfumato (the blending of edges to create soft transitions), which became a hallmark of Renaissance art and was not utilized in Byzantine iconography.

©VENIS STUDIOS

The Enduring Legacy of Byzantine Icons

The distinction between Byzantine icons and Western painting icons reveals not only the differences in artistic technique and aesthetic choices but also the profound philosophical and theological underpinnings that have shaped each tradition. While Western icons emerged from the humanist ideals of the Renaissance, which sought to bring the divine closer to human experience through realism and emotional expression, Byzantine icons transcend time and space, offering a glimpse into the eternal, untouched by the limitations of the material world.

Byzantine icons, in their divine stillness and symbolic abstraction, serve as a unique bridge between humanity and the divine, inviting the viewer into a realm where the sacred is not merely represented but manifested. They embody a theological depth that goes beyond representation — they are windows into a reality that defies human understanding, urging the faithful to contemplate not just the earthly image but the transcendent truth behind it. The formalism and iconographic rigidity of Byzantine art create a timeless language of sacred imagery that is not bound by cultural fluctuations but remains unwavering in its spiritual essence.

The richness of Byzantine iconography, with its unyielding adherence to divine symbolism, speaks to an understanding of art as a conduit for divine revelation. Icons are not just depictions of sacred figures but act as living, breathing portals to the heavenly realm, reminding us of the eternal truths that transcend our mortal existence. Through their stylized forms, the icons of the Byzantine tradition invite us to move beyond the physical world and into a sacred space where faith and the divine meet, urging us to rediscover the power of stillness, silence, and transcendence in an ever-changing world.

Thus, Byzantine icons stand not only as artistic masterpieces but as profound theological statements—symbols of eternity, sanctity, and divine presence. They call on us to look beyond the surface, to see the invisible, and to acknowledge the sacred in the everyday. In an age where art is increasingly shaped by transient trends, the timeless wisdom of Byzantine icons serves as a reminder that some truths are meant to transcend the passing of time, offering a sanctuary where the soul can seek connection to the divine.

I want to learn more:

by Venizelos G. Gavrilakis

Edited Athina Gkouma

About the author:

Venizelos G. Gavrilakis, a renowned Senior expert art and antiquities conservator and restorer one of the few internationally experts of Byzantine and post-Byzantine icons, his expertismes expand also in historical oil paintings, and Ottoman-era artwork, historical artworks and antiquities. He has been working as a senior expert conservator and restorer since 1994 for more than 30 years. He has worked with various institutions and has been involved in international conservation meetings and conferences. He has also made 3 art restoration and conservation documentaries which they have been played on TV and cinemas. Gavrilakis is the president of the art and antiquities conservation and restoration company VENIS STUDIOS, based in Istanbul, Turkey, and has collaborated with goverment departments, museums, galleries, antique dealers, and private collectors.

-

Articles: World Art News articles

Our related articles