Byzantine iconography, with its rich history spanning over a millennium, is a testament to the enduring power of visual art in the expression of faith and cultural identity. From the early Christian period through the post-Byzantine era, Byzantine art has continually evolved, influenced by changing political, philosophical, and religious currents. This article traces the key periods of Byzantine iconography, examining their development and lasting impact on the art world.

©VENIS STUDIOS

Early Christian Periods (0-312AD)

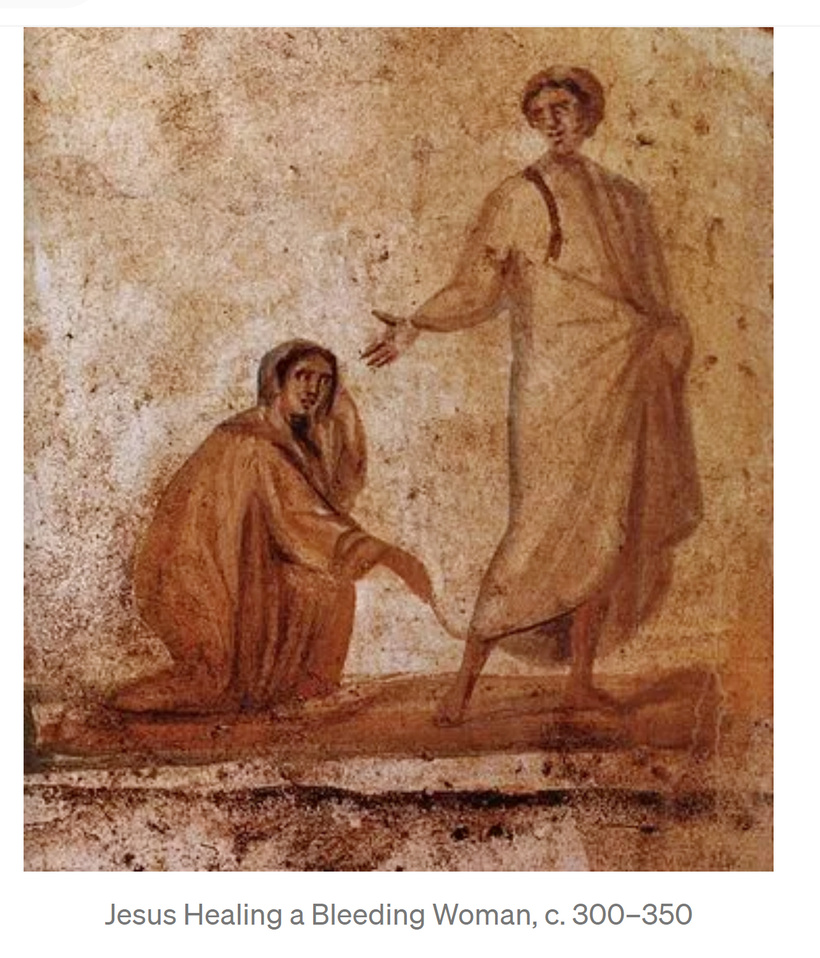

The origins of Byzantine art can be traced to the Early Christian period, specifically from the time of Emperor Constantine’s reign (c. 312 AD) until the onset of the Iconoclasm in the 8th century. The art of this time continued the Hellenistic and Roman traditions of mural painting but infused classical themes with Christian allegorical content. Christian art quickly spread throughout the Roman Empire, marking a shift from classical mythology and secular themes to depictions of biblical narratives and Christian symbolism.

During this era, the forms of art began to show a departure from classical realism toward a more symbolic representation. The focus was less on physical accuracy and more on conveying the spiritual significance of the subjects. The early Christian period laid the foundation for the development of Byzantine iconography by establishing the use of sacred symbols, such as Christ as the Good Shepherd or the Chi-Rho monogram, which would remain central to Byzantine visual culture.

©VENIS STUDIOS

Byzantine Early Renaissance (312-720AD)

The transition from classical realism to more abstract and spiritual forms occurred in the particularly through the influence of Neoplatonism and the growing Christian faith. Byzantine art evolved to focus not on the physical world, but on the divine, and this shift is evident in the iconic forms that would define the style for centuries to come.

©VENIS STUDIOS

Iconoclasm (724-843 AD)

The Byzantine iconoclast controversy, or the period of Iconoclasm, marked a dramatic break in the tradition of religious imagery. Spanning from 724 to 843 AD, Iconoclasm was characterized by a widespread rejection of images and religious icons, especially anthropomorphic representations. The condemnation of icons led to their removal from churches, and in many cases, the destruction of images of saints, Christ, and the Virgin Mary.

During this period, Byzantine art took a distinctive turn, shifting away from iconography and toward more abstract decorative motifs, often inspired by nature, such as plants and animals. The iconographic cycle was replaced by geometrical patterns and symbolic representations. Though Iconoclasm did not give rise to an entirely new art form, it served to reinforce early Christian decorative styles and further distanced Byzantine art from its classical roots. The era also marked a split between the Eastern Orthodox Church and the Roman Catholic Church, with the Pope crowning Charlemagne as the Holy Roman Emperor in 800 AD, signaling a rift in the broader Christian world and the evolution of Western medieval art.

©VENIS STUDIOS

Macedonian Renaissance (867-1057 AD)

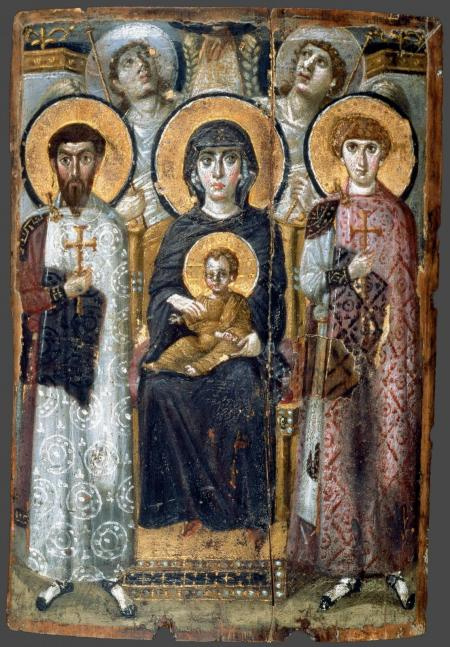

The Macedonian period, which began in the late 9th century and continued through the 10th century, is considered a major renaissance for Byzantine art. Under the Macedonian Dynasty, Byzantine art saw a revival of classical forms and motifs. The period was marked by the re-embrace of Hellenistic aesthetics, with a return to slender, elegant figures, and vivid color combinations. The figures in the art of this period were often depicted with angelically beautiful faces, graceful gestures, and a sense of spirituality that transcended physical form.

One of the central characteristics of Macedonian art was the use of golden backgrounds, symbolizing the infinity of divine light. The figures were painted with a sense of otherworldliness, and the artists aimed to convey not just the physical presence of their subjects, but their moral and spiritual significance. This focus on spirituality was achieved through the simplification of bodily features, with sensual elements such as the nose and lips being minimized to emphasize the soul’s connection to the divine.

The Macedonian Renaissance was also notable for its advancements in color usage and composition. The art became more realistic, with intense color contrasts, richly detailed drapery, and nuanced emotional expressions that began to reflect the psychological states of the figures. This period played a critical role in the development of the broad manner of icon painting, which was favored by intellectuals and the courtly elite in Constantinople, Greece, and Serbia.

©VENIS STUDIOS

Komnenian Period (1081-1185 AD)

The Komnenian period, which followed the Macedonian Dynasty, ushered in another golden age of Byzantine art. This period saw a significant shift in iconography, with an emphasis on emotion and the internal life of the figures. The Komnenian period marked the maturing of the Byzantine Renaissance, as iconography became more complex and expressive. Figures in art became less serene and more dramatic, reflecting the turbulent political climate of the time.

A distinctive feature of Komnenian painting was the intense, almost exaggerated folds in clothing, and the use of rich, contrasting colors to depict deep emotional states. The figures were painted with more dynamic postures and larger-than-life proportions, a style that anticipated later Mannerist painting in Western art. This period also saw the establishment of the iconostasis, or altar screen, in churches, a development that led to an increased production of icons as part of the liturgical environment.

Artists of the Komnenian period used iconography to convey deep emotional and theological messages, often focusing on themes of suffering, passion, and divine intervention. This heightened emotional expression set the stage for the dramatic portrayals that would define Byzantine art in the following centuries.

©VENIS STUDIOS

Palaiologan Renaissance (1204-1453 AD)

The Palaiologan Renaissance, lasting from 1204 until the fall of Constantinople in 1453, is often considered the Golden Age of Byzantine iconography. This period was marked by a revival of earlier Byzantine styles, particularly those from the Macedonian and Komnenian periods, but with a new emphasis on humanism and emotional depth. The 14th century, in particular, saw a flourishing of iconography that sought to make the divine more relatable to the human experience.

The interaction between Byzantine and Italian Renaissance artists during this period had a profound impact on the style and narrative of Byzantine art. Byzantine artists began to incorporate more vivid colors, dynamic compositions, and dramatic expressions into their work. The emphasis shifted from a purely theological representation to one that expressed human emotions—pain, joy, and reverence—in more relatable ways. This humanistic influence led to a more naturalistic portrayal of the figures, with greater attention to facial expressions and gestures.

The art from this period also became more monumental in scale, with compositions incorporating elaborate structures, dramatic landscapes, and symbolic elements such as trees and rocks that swayed in the wind. The realism achieved in this period was groundbreaking, as artists sought to present religious figures with more human-like qualities, while still retaining the symbolic nature of the icon.

©VENIS STUDIOS

Cretan School (15th–17th Centuries)

After the fall of Constantinople, the Cretan School of iconography emerged as a central force in Greek painting. Flourishing under Venetian rule, this school played a key role in preserving the Byzantine tradition while also incorporating elements from Western Renaissance art. The Cretan artists, notably Theophanes the Cretan, maintained a deep commitment to Byzantine idealism, with an emphasis on restrained movement and noble expressions. They were particularly renowned for their portable icons, which became widespread in both the Eastern and Western Orthodox Christian worlds.

Despite the influence of Western art, the Cretan School remained committed to the traditional Byzantine style, focusing on the spiritual rather than the physical. The use of light was minimal and often appeared to emanate from a depth within the icon, evoking reverence and devotion in the viewer. The portable icons of the Cretan School became symbols of piety and faith, beloved for their deeply spiritual quality.

©VENIS STUDIOS

18th Century to Present: The Revival of Byzantine Art

By the 18th and 19th centuries, Byzantine iconography began to fade as Western painting techniques took precedence. The simplicity and darker color palette of folk art emerged as the dominant artistic expression. However, there were attempts to revive the Byzantine tradition, most notably by Dionysius of Fourna in the 1700s, whose efforts were largely unsuccessful due to the prevailing Western influence.

In the mid-20th century, artist Fotis Kontoglou led a revival of Byzantine art, drawing on early Christian, Hellenistic, and Eastern traditions to reintegrate iconography into modern life. Kontoglou’s work was foundational in re-establishing the spiritual and narrative power of Byzantine art, with an emphasis on the deep spirituality conveyed through the eyes of the figures.

Today, contemporary artists continue to carry the torch of Byzantine iconography, blending historical techniques with modern sensibilities. The tradition of Byzantine iconography remains alive, respected, and influential, ensuring that the legacy of this rich artistic heritage will endure for generations to come.

The study of Byzantine iconography offers a unique lens through which to explore the intersection of art, faith, and culture across centuries. From its early Christian roots to its enduring legacy in the modern era, Byzantine art remains a critical component of the historical and spiritual fabric of Eastern Christianity, shaping not only religious aesthetics but also theological and philosophical discourse.

Throughout the various periods, Byzantine iconography transformed in response to sociopolitical upheavals, theological debates, and cross-cultural exchanges, yet it consistently adhered to a central theological and spiritual mission: to represent the divine in a manner that transcends the material world, creating a bridge between the earthly and the eternal. The shift from the classical realism of the Hellenistic era to the spiritual abstraction of the Byzantine period marked not just a stylistic evolution, but a profound transformation in the purpose and function of religious art. In the icon, the human form became more than just a depiction of the physical; it became a vessel for divine presence and a conduit for contemplation and prayer.

The periods of Iconoclasm, the Macedonian and Palaiologan renaissances, and the subsequent developments through the Cretan School and beyond underscore the adaptability and resilience of Byzantine iconography in the face of political fragmentation and external influences. Despite periods of stagnation and decline, such as the post-Byzantine era’s Westernization, the core principles of Byzantine iconography — its focus on divine light, hierarchical representation, and theological symbolism — have remained remarkably intact, carrying the tradition forward into the present day.

In particular, the mid-20th century revival spearheaded by artists like Fotis Kontoglou illustrates the continued relevance of Byzantine art. As an aesthetic and spiritual tradition, it has been rejuvenated not only as a historical curiosity but as a living tradition with the capacity to engage contemporary audiences and scholars alike. The profound emotional expression found in modern interpretations of Byzantine iconography reminds us that art can still serve as a powerful tool for connecting the human experience with the transcendent.

As we look to the future, the continued exploration of Byzantine iconography promises to shed light on broader questions of cultural identity, religious expression, and the role of visual arts in preserving intangible heritage. By examining the evolution of Byzantine iconography, we not only deepen our understanding of a pivotal artistic tradition but also gain insight into the ways in which art reflects, challenges, and shapes the collective consciousness of society across time.

I want to learn more:

by Venizelos G. Gavrilakis

Edited Athina Gkouma

About the author:

Venizelos G. Gavrilakis, a renowned Senior expert art and antiquities conservator and restorer one of the few internationally experts of Byzantine and post-Byzantine icons, his expertismes expand also in historical oil paintings, and Ottoman-era artwork, historical artworks and antiquities. He has been working as a senior expert conservator and restorer since 1994 for more than 30 years. He has worked with various institutions and has been involved in international conservation meetings and conferences. He has also made 3 art restoration and conservation documentaries which they have been played on TV and cinemas. Gavrilakis is the president of the art and antiquities conservation and restoration company VENIS STUDIOS, based in Istanbul, Turkey, and has collaborated with goverment departments, museums, galleries, antique dealers, and private collectors.

-

Articles: World Art News articles

Our related articles